This project is part of a larger Harvard GSD research initiative sponsored by the National Workers’ Housing Authority in Mexico – INFONAVIT. The studio was led by Professor Diane Davis and Jose Castillo, and I collaborated with my classmates Teng Xing and Man Su during the design. It was featured in Harvard GSD’s main gallery exhibition “Living Anatomy: An Exhibition About Housing” from August to November 2015 and was published in Platform 8: An Index of Design & Research (2015).

Oaxaca is the most ethnically diverse and culturally vibrant state in Mexico. Its historic center is a UNESCO world heritage site, but during the field trip, we were perplexed to see so many mass-produced housing estates piling up in the region’s peripheries, a lot of which were abandoned. These apartments are financed by INFONAVIT, which takes 5% of all formal workers’ salaries in Mexico and provides mortgage products for them to buy housing from developers. Failing the welfare intention of the nation’s housing program, INFONAVIT’s real estate often suffers from insufficient infrastructure, lacking communal amenities, and bad access to jobs.

The suboptimal housing provision is inevitable given the quantity-driven rationale of INFONAVIT operation. INFONAVIT is a financial agency at the national level, yet housing is a very local matter tied to each household’s specific needs. Without a regional or municipal partner, INFONAVIT can hardly gauge homebuyers’ diverse demands and provide housing options that satisfy distinct local communities.

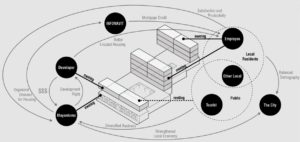

The key to making INFONAVIT work is to find an entity that operates within a specific local territory and can effectively organize individual homebuyers as a community. We thus proposed to bring the employer back to the game. Employers are excluded from INFONAVIT’s existing housing provision model, but because it is in companies and factories that workers form a lot of their social ties, employers have the social capability to better voice individual employees’ collective demand during the process of housing development. In addition, many companies own properties in the city, so the involvement of employers can also potentially grant INFONAVIT and the developers precious access to core urban locations. We thus imagined a new type of workers’ housing that is negotiated by the employers and physically constructed on top of the employers’ properties. In this model, the residential community is closely tied to the work community.

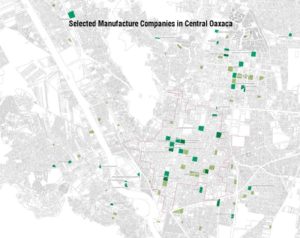

Such a “live + work” model needs to be located in urban areas in order to socially benefit the residents. If the estates are too remote, they might end up being isolated company towns where every part of the workers’ life goes around the job site – a situation we hope to avoid. Luckily, in the urban center of Oaxaca, there are plenty of formally registered small and midsized manufacture companies suitable for the new urban housing partnership. One of them is Mayordomo, a chocolate factory that we visited during the trip. Its building is located next to a vibrant pedestrian street, and like most buildings in Oaxaca’s historic center, it is constructed in Spanish-style architecture with a beautiful courtyard. The chocolate manufacturer has been expanding its business into the service industry, using the courtyard as a restaurant and event space. When asked about workers’ housing, Mayordomo’s owner said: “We paid so much to INFONAVIT, but they are not providing the housing that can benefit our employees!” So we designed around Mayordomo to explore possible ways of bringing housing back to the city center on company-owned properties.

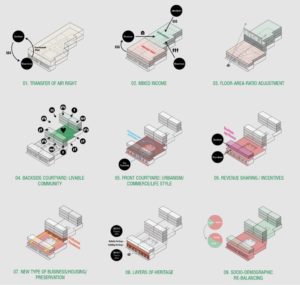

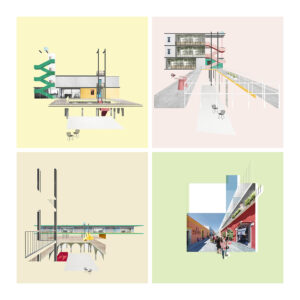

The employer-employee housing model needs to satisfy multiple objectives, including the developer’s business interest, INFONAVIT’s high-level planning goal, and the historic preservation community’s desire to keep physical alterations at the minimum. We thus proposed a series of arrangements to make the model feasible. The City first needs to rezone the site to increase its Floor-Area Ratio, after which Mayordomo can auction off the development right above the chocolate factory – this revenue is also an incentive for the employer to join this housing partnership. The developer shall build two types of housing on top of the factory, one for Mayordomo’s workers, subsidized by INFONAVIT, the other sold at market rate, producing profits for the developer. The workers’ units are at the back, forming an intimate community. The market-rate housing faces the street, but in order to reduce the visibility of tall structures on the historic site, the market-rate housing will be kept at a lower FAR. The developer can compensate for the loss of FAR by operating these market-rate units as high-end properties, which enjoy great access to the fully renovated roof deck and the commercial courtyard of Mayordomo. The expanding business of Mayordomo and the market-rate housing units reinforce each other: Mayordomo provides services and entertainment activities to the developer’s residents, and the developer brings customers to the chocolate company. For the city as a whole, this model enhances Oaxaca’s economic development by gradually bringing the residential population back to the city, expanding business opportunities for traditional crafts, and creating a unique urban experience that attracts tourists.

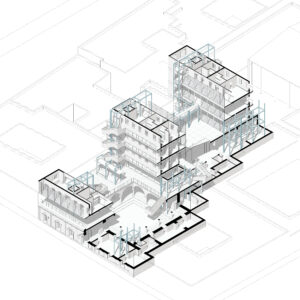

This housing development model puts formerly isolated public and private partners into the same space, and we further used our design to explore what new social relationships can emerge out of this spatial arrangement and what kind of architectural quality the interactions will imply. Although the project is first and foremost concerned with housing, we believe that open space is crucial for the social wellbeing and spatial pleasure of housing development. Therefore, in the Mayordomo house, we investigated the creative potential of courtyards, using architecture as a lens to imagine what it could mean for both the tourists and the local residents to use the courtyard and how traditional cultures will meet new businesses in the courtyard.

Ultimately, by tackling courtyards as the spatial and programmatic tie between living and working, between tradition and innovation, and between domesticity and public life, the project envisions a more ambitious network of hybrid urban spaces for Oaxaca. What if more companies join the housing partnership? How will the historic center be different but at the same time familiar? The Mayordomo case is generalizable because 1) the courtyard building of the chocolate factory is representative of the architectural typology in the city and 2) there are many other similar companies suitable for our proposed housing partnership. By proposing to build housing on top of company buildings and to form strategic partnerships between the employers, developers, and INFONAVIT, we hoped to provide the federal agency with new ways of thinking about housing and its relation to the city.